Pahalgam Incident, a Pretext to Undo the Indus Water Treaty

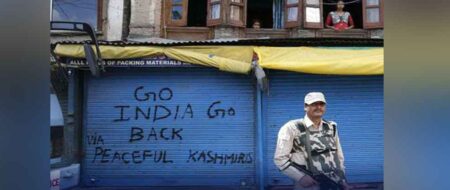

On April 22, 2025, Indian tourists visiting Indian Illegally Occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IIOJK) were attacked in Pahalgam, Anantnag District, resulting in the deaths of 26 individuals. A previously unknown militant group, calling itself the ‘Kashmir Resistance’ or ‘Resistance Front,’ claimed responsibility. However, India’s military intelligence has yet to find any evidence of such an organization operating in IIOJK.

However, without producing any evidence publicly, India claimed that a Pakistan-based terrorist organization sponsored the attack. Pakistan has denied any involvement in the attack, expressed grief over the killing of innocent people, and condemned the loss of life. Pakistan also proposed the establishment of an independent forum to conduct a formal investigation into the incident and expressed its complete willingness to cooperate with the inquiry.

India’s Action and Pakistan’s Well-Thought-Out Response

Without establishing the factual position of the incident, India announced a string of punitive actions against Pakistan. The most threatening and alarming is the suspension of the crucial water-sharing treaty, the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) of 1960. Responding to India’s uncalled-for actions, in a high-level meeting of the National Security Committee, the Pakistan government also decided to impose a series of retaliatory measures, including closing down its ground links and airspace to India’s commercial flights destined for the Middle East and possibly Europe.

Moreover, in a strongly-worded statement, the Pakistan government warned that any attempt to block or divert flows of rivers into Pakistan would be “considered an act of war.” Pakistan described it as a “vital national interest” and a lifeline for the country’s 240 million people. The statement also expressed that “Pakistan shall exercise the right to hold all bilateral agreements with India, including but not limited to the Simla Agreement, in abeyance, till India desists from its manifested behavior of fomenting terrorism inside Pakistan, transnational killings, and non-adherence to international law and UN resolutions on Kashmir. Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif also reiterated Pakistan’s position during his address to the newly commissioned officers at the Pakistan Military Academy on April 26.

Indus Waters Treaty 1960: A Brief Background and Its Possible Future

Water sharing between India and Pakistan has been an irritant since 1947. During the early 1950s, the tension between the two over water distribution attracted global attention. With international mediation led by the World Bank, both countries achieved a rare diplomatic victory and signed the IWT on September 16, 1960. According to the treaty, six rivers of the Indus River System (IRS) were divided into two groups: the Western Rivers (Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab) and the Eastern Rivers (Ravi, Bias, and Sutlej), and were allocated to Pakistan and India, respectively.

According to the terms of the treaty, India exercises full rights over its allocated rivers, while on the Western Rivers, two clearly defined leverages were granted to India: One, India will continue to irrigate those areas from these rivers which were so irrigated on the effective date after the treaty and was allowed to make further withdrawals to the extent as it may consider necessary, leaving the volume to be withdrawn solely to the discretion of India. Two, India was allowed to construct as many dams as it wished without clearly defined structures, thus potentially creating a ‘loophole,’ allowing India to overexploit the rivers. The main focus of the treaty was to manage the IRS’s surface water through a formal setup. Yet, since we live in a realist world, the IWT laid the foundation of the ‘zero-sum’ approach.

Current Status and Possible Future of the IWT

Currently, the world continues to face pressing challenges on the issue of water. Both India and Pakistan are among the world’s most water-stressed countries. Thus, the IRS is essential for India and Pakistan, and it must be handled carefully by preserving the sanctity of the rare diplomatic victory of the IWT. Nonetheless, the IWT, a pillar of stability in South Asia, which also survived two full-fledged wars between the two countries, is now under attack.

The risk of hydropolitical tension is increasing in the region, against the spirit of scholars’ suggestion that sharing water should not be a zero-sum game. India is already violating the IWT and might experiment with revoking it altogether, putting Pakistan’s survival at stake. The situation could lead to a worst-case scenario where Islamabad might be compelled to react without separating the two issues, namely water and Kashmir.

Since the early 1970s, India has contemplated launching hydel power projects (HPPs) on Western Rivers, with a cumulative power generating capacity of 32,000 MW. A report published by Climate Diplomacy confirms that the majority of over 70 planned dams fall in the category of large dams, which would threaten peace and security in the region in the event of armed conflict over the issue between the two countries. Besides, “climate change on the Himalayan glaciers would also increase the likelihood of disasters across the region, having implications for future interstate cooperation and regional developments.”

Since the early 2000s, Pakistan has regularly raised objections over the design parameters of the dams that India continues to construct on Pakistan’s rivers. There is a long list of disputed HPPs that India has either completed or are in the pipeline, and the Wullar Barrage is one of the burning issues. Presently, the two HPPs, Kishanganga (330 megawatts) and Ratle (850 megawatts), located on tributaries of the Jhelum and the Chenab rivers, respectively, are the primary source of concern for Pakistan. Kishanganga was completed in June 2018. It is designed to divert water from the Kishanganga River, known as the Neelum River in Pakistan.

A former chairperson of the Tennessee Valley Authority has opined that no army with bombs and shell fire could have divested a land so thoroughly as Pakistan could be devastated by the simple expedient of India’s permanently shutting up the source of water that keeps the fields and the people of Pakistan green. We have a live example as Bangladesh is suffering badly because of India’s well-planned strategy of diverting the Ganges water by building the Farakka barrage on the river.

It is believed that the sanctity of the IWT, which survived for sixty years, is being eroded, and problems related to the subject are emerging rapidly for multiple reasons. India’s recent upstream water infrastructure projects, coupled with the territorial conflict over Kashmir, have rekindled conflicts and continue to undermine the treaty.

The treaty, in its present form, is fragile. In the absence of an independent monitoring mechanism, India continues to manipulate the treaty in its favor. Since 2016, India has been trying to find excuses to ‘punish’ Pakistan. In September 2016, during a formal meeting, Mr. Modi came out blustering and threatening that “blood and water cannot flow simultaneously” and stated that the IWT should be re-evaluated.

In 2021, India’s parliamentary standing committee urged the government to renegotiate the IWT, citing ‘missing links’ in the original treaty, like climate change and the environmental impact assessment, as justification.

In 2023, the treaty came back into the spotlight when India served a notification to Pakistan under the provisions of Article XII (3) of the IWT for modification to the IWT in retaliation for its noncompliance with the dispute resolution mechanism and persistent objections regarding Kishanganga and Ratle HPPs and demanded a response within ninety days. India also mentioned “climate change as a significant factor in its decision to alter the IWT.”

Pakistan has officially responded to India’s notice. While referring to Article XII of the treaty, Pakistan emphasized that “the existing treaty will continue to reign unless the parties to the dispute – Pakistan and India – bilaterally introduce changes to the pact.” The response further concluded that the “sanctity of the existing Indus Waters Treaty cannot be damaged between the two nuclear countries, and the whole world cannot afford it.”

The IWT, in its current form, predominantly serves India’s interests. However, it is widely believed that India may exploit the Pahalgam incident as a pretext to advance its broader strategy to address its growing water challenges. For India, abrogating the IWT remains a viable option for securing future water needs. The treaty is under mounting pressure, and its potential collapse would mark a rupture with profound symbolic and strategic consequences. In this context, the need for water rationality and cooperative management has never been more urgent. At present, the responsibility for preserving peace and stability in the region rests squarely with India.

The Possible Consequences

Pakistan’s irrigation system is facing difficulties and shrinking due to several factors. Thus, the changes in the existing treaty by India could disturb the water flow into Pakistan, badly affect its agro-based economy, and adversely affect its HPPs and the resultant livelihoods of its people. Besides its impact on Indo-Pak relations, the treaty’s modification could also have a broader impact on regional stability, as water resources are becoming increasingly scarce and contested in South Asia.

Without a backdoor diplomatic channel, the situation can go out of control. Presently, it appears that there is no discreet communication channel that could defuse the situation. India’s fiery media would make it difficult for Modi to act rationally. Besides, Modi, a member of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), could act irrationally. However, the media would act as a catalyst to expedite the process of destabilizing the region by engaging in an act of war with Pakistan. Though Trump has publicly refused to involve himself in the current crisis, his administration has already expressed its support for India by condemning terrorist acts, which might encourage Modi to go ahead with his maligned intent of destroying Pakistan by strangulating its agriculture sector, which is the lifeline for Pakistan.

The last major crisis that took place between the two countries occurred in 2019 when some Indian security personnel were killed in the IIOJK. After the attack, India launched an air strike inside Azad Kashmir that stopped just short of an all-out war. It was managed, but who would guarantee that the current confrontation would be managed again? In the absence of any role by a third party, the crisis could intensify beyond the 2019 standoff. India has already moved on the path of escalation by firing across the Line of Control, which could turn into a full-fledged war between the two nuclear-armed states. The consequences of the escalation could lead to a catastrophic end, having regional and international implications.

The Way Forward

We already have enough disputes/crises in the region; we cannot afford to have more in the form of a possible ‘water war’ between India and Pakistan. The two countries need to work collectively to address the issues related to water management in the region. The IWT, in its preamble, promotes the spirit of goodwill and friendship for the utilization of the IRS; it must be applied by the two countries in letter and spirit.

Though Pakistan’s limitations and the possible consequences of entering into re-negotiation are understandable, this does not mean that we should keep on losing ground under the existing treaty in the hope that a miracle will happen to keep the treaty on track. Pakistan will keep struggling, but it will have to respond one day, and then it will be too late. Hence, Pakistan must abandon its wait-and-see policy and take a bold step to respond positively to India’s notification while taking all precautionary measures. As some scholars suggest, China and Afghanistan, being regional players, also share the IRS and are becoming increasingly relevant over time. Hence, they may also form part of the re-negotiation process by enhancing the scope of the IWT.

It is understood that negotiation on a subject like water is a very complex and time-consuming process and might take ten to fifteen years to reach a logical conclusion. It may or may not succeed; thus, until an agreement is finalized and ratified by the two parties, the sanctity of the IWT must be maintained to avoid a crisis-like situation emerging in the region. During re-negotiation, India must freeze the work on all ongoing and planned projects on the Western Rivers.

To ensure the continued effectiveness of the IWT, whether in its original or a renegotiated form, an autonomous Indus Waters Commission should be established under the auspices of the United Nations. This commission should comprise neutral experts drawn from global institutions beyond South Asia. As a sovereign body, it must be equipped with adequate resources and authority to guarantee that the treaty, whether preserved or updated, is implemented faithfully and in full accordance with its original spirit.

As frequently highlighted at various forums, Pakistan cannot rely solely on its current arrangements to address its growing water scarcity. Pakistan still has an opportunity to avert an impending water crisis by formulating a comprehensive backup strategy, incorporating both short- and long-term measures that have been widely discussed at the national level. Decision-makers must recognize that pursuing short-term political gains at the expense of long-term water management planning will not serve the nation’s interests. Pakistan must take the lead from China, which has constructed approximately 87,000 large and small dams, earning it the title of “the Water Tower of Asia.” Similarly, India has built over 5,000 dams, including 447 which are classified as major structures. Against this backdrop, the question arises: Who is responsible for Pakistan’s looming water crisis? It is a pressing question that policymakers must urgently and honestly address.

Conclusion

To conclude, the world is already suffering as a result of the war between Russia and Ukraine. The Middle East crisis is even worse, in which over 52,000 Palestinians have been killed and more than 100,000 injured, mostly women and children. Moreover, around two million people from the Gaza Strip have been uprooted from their homes, having no food, water, shelter, healthcare, or schools.

Hence, the world cannot afford yet another war between two nuclear weapons states. Pakistan and India should, therefore, sit together and find amicable solutions to the ongoing disputes in the interest of the over 1.66 billion people of this region. The two countries jointly have the potential to produce enough food to address the emerging challenges that the world is likely to confront in the foreseeable future.

Dr. Muhammad Khurshid Khan SI (M) is a retired brigadier of Pakistan Army and a fellow of the Stimson Center, Washington D.C.